About GamePeople

About GamePeople

Subscribe to the Faithful Gamer column:![]() RSS or

RSS or

![]() Newsletter.

Newsletter.

Format:

Board

Genre:

Shooter

Style:

Firstperson

Buy/Support:

Support Andy, click to buy via us...

Train is a very unusual game, a one off board game that puts players in charge of death camp transportation, but what implications does it have for videogames?

If board games are the antithesis of videogames, Brenda Brathwaite's Train is perhaps the least likely of them to appear in a video game magazine. But although it is a very different experience, it exemplifies how games can escape being predictable, safe or self indulgence. It's also an intriguing example of a game that is widely trusted to address a difficult subject.

Train is a tabletop game played on a pealing window frame laid flat in front of the players -- complete with freshly broken panes. Across it lie three railway tracks, each with a set of carriages that can transport a set of yellow wooden people. A typewriter sits nearby with a piece of paper sticking out. Pulling the sheet from the mechanism, players find a set of rules that instruct them to load the people into the boxcars and progress to the end of the track. To do this they roll dice, draw cards and make choices that result in switching tracks, damaging trains, or derailing - as well as the desired forward progression.

If you've heard about the game before, you probably already know the ending -- you see, the destination revealed by the terminus cards at the end of each track is Auschwitz, or another Nazi concentration camp. But it's not this final reveal that makes Train significant and interesting. Unlike games where the twist is the main emotional content, Train creates an uneasy complicity of the player's actions as they collude in the transportation.

As you can imagine, Train is an unusual game and this results in an unexpected experience for the players. On one level, its one-off nature separates it completely from the mass produced videogames we play. But on another, it claims many design and cultural successes that gaming should take note of.

Far removed from focus groups or big business, Train grew from a conversation between its enigmatic designer, Brenda Brathwaite, and her seven year old daughter. I asked Brathwaite how this came about. "She had been learning about the Middle Passage as part of Black History month at her school. When I asked her how she felt about it, she was super-light in her answer. She used the right words but there was no real understanding. I wasn't expecting her to be really upset but I was expecting some sort of connection."

Brathwaite continued what was obviously an often-told story, "discussion over, she wanted to go and play a game. I spontaneously reached for my prototype game pieces and put a little game together about the Middle Passage. In the game I asked her to create families from the little wooden pieces for about half an hour. Then, using an index card as a boat I started to load random handfuls of pieces and set off across the sea."

"My daughter's reaction was 'you've left people mummy', as she tried to put the other pieces on the boat. 'But they want to go' she said. 'Nobody wants to go honey, this is the middle passage' I answered."

Brathwaite's tone makes it clear this is a personal and moving moment.

"She looks at me as if my game doesn't make any sense. 'Trust me, I tell her'. Then, about halfway across the ocean, she's rolling high and realises that her food is running out. 'What are we going to do mummy?' 'We can either put some people in the water' I tell her 'or we can go on and hope they don't get sick.'"

Brathwaite's tone makes it clear this is a personal and moving moment. "She instantly realised what I meant and asks 'Mummy, did this really happen?' And we have this amazing discussion about how brothers and sisters might have been separated and daddies could have come out of the woods and find the mommies gone. She was blown away that this really happened, by simply spending times with these abstract figures."

This story is obviously a powerful one. Not just for her daughter, but for Brathwaite herself. It was a moment that set her on a course to create what became the set of games that explore difficult and emotional subjects.

Within a week she had six game ideas. The New World, the Middle Passage game; Siochan Leat, a game about the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland; Train, about the death camps; Mexican Kitchen, about illegal immigration workers; One Falls for Each of Us, about the forcible relocation of Native Americans; and finally City Solet, about the day and night life in Haiti.

Train is the game that currently stands out. It's the most recently finished, and of course has a headline grabbing topic. Brathwaite made it clear that this was no ticking of boxes though. "Of these games, Train was one I had to do. If you are going to do games about difficult topics you can't avoid the holocaust if you want it to be a full exercise."

Hearing Brathwaite describe this process, it's clear that these games result from a coming together of her personal and professional life. There is something genuine, in an artistic sense, about her use of game prototyping tools to respond meaningfully to this moment with her daughter.

Big budget videogames usually chase much bigger, grander ideas. As Brathwaite talks about Train I'm reminded of the small scale independent game makers. The likes of Braid and Everyday Shooter that are limited by time and money, but none the poorer for it. They are able to offer something much more personal and intimate - something that results from their desire to make sense of events in their life.

Should we be making games about these difficult subjects or not?

Flower on PSN is another interesting example (see boxout). It was a game that developed as a response to Creative Director Jenova Chen's recent life. He had recently moved from the metropolis of Shanghai to the greenery of LA and wanted "to try to capture that feeling with an interactive experience."

Perhaps Flower is such a fresh game because it was born in response to everyday life. Like Train, it shows these small scale ideas are great at creating connections with players. They feel genuine because they are genuine -- the desire to make sense of the world using the tools of our age.

Alongside this personal moment in Train's conception runs Brathwaite's professional life. Her story of the game continues along these lines. She was having dinner with another professor and a high school teacher and Zig Jackson was at their table -- the Native American photographer. He was talking about visiting a reservation after a shooting and how he "found that he simply couldn't take any pictures". Although a photographer, confronted by such a difficult setting he was almost unable to do what was most instinctive.

Brathwaite reflected on the conversation. "Listening to him and another photographer discuss whether they should take a picture or not, it occurred to me how many times we don't make the game because we think the subject matter is not suitable. I had this transformative experience, as I thought along similar lines: Should we be making games about these difficult subjects or not?"

Here, Brathwaite changes gear from the warm emotion of her mother daughter moment to something more analytical. "So often we make games because it's fun or commercially successful. But how many paintings are painted with that in mind? Or how many great works of art exist that didn't have to ask that question? It was simply the medium of expression that the artist selected."

Creating Train as a board game enabled Brathwaite to side-step industry and cultural expectations of videogames. "I made these games non-digital" she says with a knowing tone "because videogames right now are a very loaded thing. Videogames come prejudged, but board games remove this baggage from the discussion."

"We're not at a point where people are making videogames as social commentary -- certainly not as much as comics or editorial. This is partly because of the amount of time and effort that goes into a videogame. That's changing with the art-game movement and how games integrate moral choices. But the baseline assumption about videogames is that they are entertaining, fun and light."

Board games create experiences that invite the player to interpret the analogue experience for themselves.

As players we of course know that game aren't only about having fun -- that there is often something much deeper going on. But as Iain Simons (see boxout) co-founder of the National Videogame Archive told me, this isn't the face of gaming that is presented to the wider culture. For him, games need to "stop apologising and start participating -- because it's not enough just to make a brilliant, meaningful and significant game."

Even when games like Silent Hill Shattered Memories make efforts to question and deconstruct the choices we make -- by shaping the game around those decisions for each player -- they are still sold as traditional survival horror games. These games don't yet have the confidence to let the social, political or ethical issue sit centre stage.

Of course, a big part of this reluctance is the level of investment required to get a videogame to market. Brathwaite's ability to easily riff on her game ideas enabled her to quickly create a workable prototype for her daughter in a way that would be difficult with a videogame. This not only made it easier to see how ideas worked, but also it seemed to grant her permission to see how it felt addressing more difficult subjects.

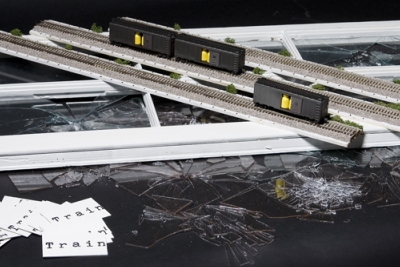

Fig 3. Screen shots for Train.

"The same thing could have happened with a videogame if I had been able to spontaneously program a game on the spot. But it would have missed some of the tactile elements. You still make connections to digital things -- I have a WOW character that I care a lot about. But I really believe there's a tremendous thing that happens when it's just the players and the rules and you are able to touch all the individual parts."

This understanding about the unique experience a board game offers, and how this is different from a videogame, runs through Brathwaite's passion for physical interactions. Board games create experiences that invite the player to interpret the analogue experience for themselves.

"Train, for instance, couldn't be programmed because of the way it enables the infinite possibility of the human imagination. Take the Derail rule for example, 'When the car derails half the pieces return to the starting gate and half refuse to re-board.' What does that mean? Some players have said the people are dead and have laid them down on the board, others have said they've escaped, while others have forced them to re-board. As players make this range of individual decisions they are implicated in the outcome. Train takes full advantage of this analogue luxury."

To a videogame player this may sound like the rules are loose. But Brathwaite was quick to correct me on this. "There's no looseness in Train's rules. I literally agonised over every single word in that ruleset. If you consider the allowable gamespace created by the rules, I was aware with every single stipulation I was changing the shape of this space. Instead of designing to close out rules lawyering, I designed knowing people were going to do it. There are these intentionally designed gaps in the rules that let the players decide how they will bridge them. The rules are then waiting for them on the other side when they have made up your mind."

Because of their binary nature, it's hard to imagine a videogame achieving these genuine gaps in gameplay where the player can essentially make their own way forward for a short spell. As Brathwaite puts it, "This is not possible in a videogame if you are to allow for the infinite possibility of what someone might do."

These gaps cleverly mirror the tactile nature of Train, which is in itself an invitation for players to choose how to move pieces around. "Before players know what Train is about they often take the pawns and just slam them into the train-cars." And here there is a sense of sombre glee for Brathwaite, that the game is affecting the players so thoroughly. "But when they realise that they represent the Jews, they take them out of those cars and set them down so incredibly gently."

Conjuring pictures of a craftsperson intricately applying finishing touches to a painting or novel, Brathwaite describes her setup devotions.

Seeing pictures of the game, you are unaware just how precisely it is setup each time. The importance of the arrangement of the game pieces is something that Brathwaite is meticulous about. "I set the game up in a very ordered way. Perfect order digitally just doesn't look as interesting or collar intention as much as in an organic world space."

This is another difference between the physical and digital space. "Walking into a shop after someone has perfectly ordered the shelves really takes you back in a way that wouldn't surprise you in the least in a videogame."

Conjuring pictures of a craftsperson intricately applying finishing touches to a painting or novel, Brathwaite describes her setup devotions. "When I setup Train there is a good 20 minutes when I'm making sure everything is perfectly aligned, without a piece out of place. That regimented order is then followed by the players -- as well as looking surreal." Hearing this makes me realise that Train is as much a piece of art as it is a game. It's as much about a temporary physical performance as it is about winning or losing.

This performance aspect of Train takes us furthest from videogames. Not just because of its one-off nature, but because of the way people don't play videogames in front of onlookers anymore.

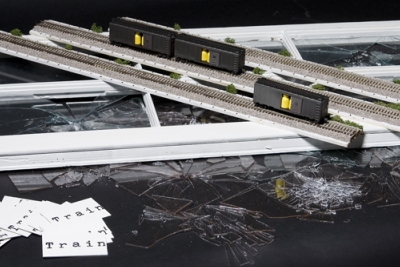

Fig 4. Screen shots for Train.

"When a player flips over a card at the end of the game and realises it's an extermination camp, the way they feel couldn't be replicated online. Sitting there with other people watching and supporting you is both unique and moving. That kind of face to face interaction -- not to mention the hours of discussion that often follows -- simply can't happen online."

Perhaps videogame's recent reticence to local multiplayer experiences could stand some correction here. For Brathwaite the tactility and local nature of the gameplay go hand in hand in a way that videogames simply can't recreate. "Although they are using the same basic things and share a tremendous amount -- play and interactivity to create meaning -- the outcomes of board games and outcomes of videogames are unique to each platform. Train specifically designs towards these strengths."

In many ways Train's limited nature and scarcity takes us back to days when arcade games dominated. Not only would you have to travel to play them like you would a piece of art, but that experience of play could then only be had in a public space. As you played a particular game a small crowd would often gather to watch, share and pass judgement on your progress.

Maybe [viodegame's] coverage is at first clumsy but at least we are covering it.

Brathwaite seemed comfortable with the analogy, "we recently went to Bar-cade in Portland, full of old arcade games. It was really interesting in terms of the scarcity of it. That concept of scarcity of the older days still exists. But the unique thing about Train is the invitation to implicity that a videogame simply can't recreate."

Pushing back a bit, I ask about Modern Warfare 2 involving the player in its Airport hijack. "When Modern Warfare 2 came out I was bombarded by comments about the Airport scene. I think it's a good thing that games are exploring spaces like that. I view it as a sign of a maturing media that we are starting to cover these things. Sure, maybe our coverage of them is at first clumsy but at least we are covering it. I think games have the same editorial potential as any other medium. Players seem to have had an artefact left in them from it."

But, even with her generous descriptions of Modern Warfare 2, it's clear that Train has very different ambitions. This is more than wanting more meaning injected into a game, but a desire to question the fabric of the player themselves.

"The larger question in Train is: Are you just going to blindly follow the rules? Even if you have just taken them from a Nazis typewriter, will you obey them without even asking where it is all heading? And the answer is yes, in the case of Train at least, we will."

It's a sentiment and ambition that reminds me of the TV series The Wire. Train, like David Simon's show, masquerades as something straightforward and unproblematic. But scratch beneath the surface and it is much more mature and challenging. You can see it in the way Brathwaite talks about the broad themes of Train. But, maybe moreso, you can see it in her detailed approach - like Simon's says of The Wire this is something where "every piece matters".

And it seems to have been a transformative experience for Brathwaite as well. "One of the ways this series has really changed me is the realisation that every design decision matters. I don't rush any aspect. If you see a detail on Train, it's there for a reason -- not just so I could finish the thing. I've tried to take that level of discipline into my professional life in videogames."

Train reminds us of the potential of games, that they can be something that meaningfully responds to our individual life experiences.

Looking at the game close-up is impressive. Not just the finishing details, but how the pieces relate to each other, their proportions, design and function. The wooden yellow people for instance, are just small enough to fit through the carriage doors, but at the same time big enough for the player to have something of a wrestle to get them out again. It's a small detail, but one that clever implicates players in Train's theme.

It's these details, as Ian Bogost describes in his Gamasutra article, that result in meaningful gestures for players. "Simple, trivial acts like picking up game tokens or moving pieces along the board take on rich multiplicities of meaning in the minds of players and spectators alike thanks to the game's striking ambiguity."

David Simons is famous for saying "you have to get the detail right or it's just TV", Brathwaite certainly echoes this with her own meticulous attention to detail on Train. But for her, it's levity she avoids rather than soap opera. Train's minutiae create a weighty experience that avoids just being about winning.

Encountering Train is a mind stretching experience. But as well as being awe inspired by its cultural depth and weight, there are plenty of interesting implications for our electronic experiences, as well as some things that are impractical to translate.

Train reminds us of the potential of games, that they can be something that meaningfully responds to our individual life experiences. It shows us how players are involved in game experiences, as much by the space left for their imagination as by the detail of what is included.

It reminds us that physical gestures are not only useful to control a game but also reflect how we feel about it. And finally, it questions videogame's recent reticence of playing together in the same space, suggesting our rush online is missing something fundamental about how people really want to play together.

There is nothing to stop videogames gaining a similar social status.

And running through all this is the longer story of the time it takes for media to really be trusted by our wider culture. Videogames are still in their youthful phrase, and society is understandably suspicious of their motivations. As Iain Simons suggests, if this is going to change we need to stop defending our videogames and start participate in broader culture.

It's this acceptance and conversation around Train that most distinguishes it from a videogame. A board game about the death camps is intriguing it seems, whereas a videogame about them is threatening. Rather than Train's tactile nature, analogue rules and art exhibit sensibilities, maybe it is its ability to be trusted that videogames should really take note of.

While much of Train's genius is specific to the board game media, there is nothing to stop videogames gaining a similar social status. It will take time and commitment, but that trust is quite possible to build -- if that's really the place we want games to be.

Second Opinion from Iain Simons

Although videogames are often talked about in terms of art, the conversation isn't usually taken beyond a defence of our hobby. One exception was the Non-Trivial Interaction weekend that ran at the Southbank National Film Theatre in London. Iain Simons (who directs the GameCity festival and co-founded the National Videogame Archive) came up with the event to explore the boundaries between videogames and film from the perspective that games are culturally important because they are part of our everyday lives.

Simons asks similar questions of videogames that have motivated Brathwaite's project. "The event was about beginning to expose developers to the broader culturally interested public." The public event offered opportunities to experience games as well as talks around the subject of Non-trivial Interaction. It was step towards presenting videogames as something that participated in broader culture and has continued more recently under the guise of Nottingham's annual videogame festival, GameCity.

As Simons puts it, "videogames are lots of things culturally, but to date they don't contain the detail or narrative nuance that film can deliver. What they are, as well as sometimes being interesting in and of themselves, are a great platform for engaging the broader public and new audiences in dialogue about themes which they contain and suggest. Videogames and moreso the games industry itself has a long way to travel to catch up with engaging the public about something other than just trying to get them to buy their game. The industry is startlingly bad at participating in broader culture."

It's not a big leap to see why a designer like Brathwaite is aware of the additional baggage there would be to design her series on difficult subjects as videogames rather than board games.

"I think videogames are probably really quite good at dealing with difficult subjects, but in order to do so credibly they need to establish some trust with the broader commentators. If we look at the games that have really reached toward tacking something difficult the dialogue has stalled when the mainstream is unable to grant any trust in the claimed real intentions of the devs."

"I'm thinking about Manhunt, Modern Warfare 2, do I trust that these developers and publishers are really trying to make me think about my complicity in the voyeurism and violence debate in more interesting ways? I'm not sure, it's kind of like if Michael Bay had made Saving Private Ryan rather than Spielberg."

"And the right wing media certainly doesn't trust them. Some of this is unfair, misplaced, lazy prejudice - but if we're going to fight that we need to participate meaningfully in the debate and actually mean it when we say it."

Of course, our experience tells us that videogames can be significant cultural experiences. But games need to find the confidence and commitment to join the wider cultural debate in an ongoing way. As Simons puts it, "stop apologising, start participating -- because it's not enough just to make a brilliant, meaningful and significant game."

First published in GamesTM Issue 102 on-sale 28th October

Andy Robertson writes the Faithful Gamer column.

"Videogame reviews for the whole family, not just the kids. I dig out videogame experiences to intrigue and interest grownups and children. This is post-hardcore gaming where accessibility, emotion and storytelling are as important as realism, explosions and bravado."

© GamePeople 2006-13 | Contact | Huh?

|

Family Video Game Age Ratings | Home | About | Radio shows | Columnists | Competitions | Contact

With so many different perspectives it can be hard to know where to start - a little like walking into a crowded pub. Sorry about that. But so far we've not found a way to streamline our review output - there's basically too much of it. So, rather than dilute things for newcomers we have decided to live with the hubbub while helping new readers find the columnists they will enjoy. |

Our columnists each focus on a particular perspective and fall into one of the following types of gamers:

|